Elva Motor Cars

She Goes!

Sixty years ago, the "Elva" marque came to the scene and, for a decade, was one of the world's most successful makers of production racing cars. During a period of roughly 10 years, beginning in 1955, Elva cars enjoyed enormous success in competition but since most of it was in the United States, the marque remained relatively undervalued in Britain.

Lotus, Cooper and Lola were the firms that captured the imagination at home, mainly because they were successful in the single-seater categories. Elva was content to concentrate largely on production competition cars, attempting to establish itself on a sound commercial basis.

Frank Nichols, the marque's founder, recalls, "Every year I'd write to L'Automobile Club de l'Ouest asking how much they were prepared to pay in starting money for my cars to take part in Le Mans and every year they'd write back and tell me that competing was reward enough. I couldn't run a business on those terms."

In the strictly amateur racing organised by the SCCA, however, Elva competed on equal terms with its rivals and there the firm enjoyed its greatest successes both in terms of wins and of sales. In 1960, for example, Formula Junior was dominated by the works Lotuses of Jim Clark, Trevor Taylor and Peter Arundell.

Elva Courier in front of the Factory

The success of these three brilliant drivers soon convinced everyone that the only way to win in FJ was with a Lotus or a similar, rear-engined, British car. In America Charlie Kolb swept everything before him in his front-engined Elva-BMC that everyone in England knew to be hopelessly out-dated. It was lust as well that Kolb apparently didn't know. Kolb's rivals had access to the latest machinery and so it was a fair and square win, but it was one that went almost unnoticed here.

When Jim Clark led the 1962 Nürburgring 1000 kms in his 1.5-litre Lotus 23-Ford it rightly created a sensation. When, the following year, a 1.7-litre Elva-Porsche won the prestigious Elkhart Lake 500 sports car race, it was, if not an equal feat, one which was worthy of comment. In the States it led to 15 immediate orders for cars yet it caused scarcely a ripple in Britain.

The trouble is that all marques of the time tend to be overshadowed by the innovative genius of Colin Chapman and Elva cars tended to be just a step behind Lotus. When the Elva VI, a little rear-engined sports car, first underwent testing in late 1961. it easily lapped under the Goodwood record. Then, at the Boxing Day Brands Hatch meeting, Chris Ashmore created a sensation by latching his 1,100 cc Elva VI-Climax onto the tail of Graham Hill's 3-litre Ferrari. A couple of weeks later, though, the new Lotus 23 went testing and showed itself to be even quicker.

The difference between Lotus and Elva was that Lotus was headed by a designer who was backed by excellent accountants who managed to keep the business going leaving Chapman to explore his art and be almost reckless in his ambition. By contrast, Frank Nichols of Elva was a businessman who limited his company's activities in order to sell racing cars profitably. In practical terms that meant no wholly-supported works teams and, following on that, no employment of the very best in driving talent. It meant no forays to Le Mans, say, and certainly no involvement in F2 or F1.

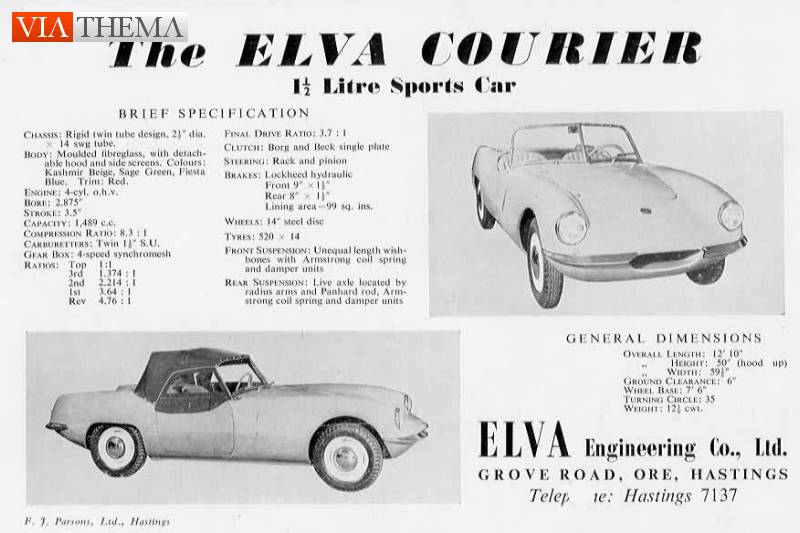

Elva Courier Publicity

Nichols had always been interested in motor racing so when his business was sufficiently prosperous he decided he'd have a go himself. In late 1953, he commissioned a special from Mike Chapman of Hastings and while it was building, bought a second hand Lotus VI with which to gain some experience.

Mike Chapman's car, the CSM was delivered late in 1954, a typical special of its time with a space frame, a simple aluminium body styled along Lotus VI lines, a Ford split front axle and a coil spring-suspended beam rear end located by a Panhard rod. The engine was lingered down from 1,172 cc to 1,100 cc, a special camshaft fitted and transmission was via Buckler close ratio gears. Frank's was very much a "blood and guts" approach, with the throttle either fully open or shut. There was nothing in between, no subtlety. It was a technique which did not lend itself to wet conditions which, not surprisingly. Nichols hated.

A shrewd man, Nichols soon lent his car to John Bolster who wrote glowingly about it in Autosport, mentioning the possibility of replicas to be sold in kit form for around GBP 500. This upset Colin Chapman who threatened to sue for infringement of copyright on the grounds that the car used a space frame. Frank's reply was roughly translated. "Seek ye the sage and the onion". The idea of the space frame had anyway, been around for quite some time though it has to be said that the CSM did bear a resemblance to a Lotus Six except that it used a torque tube.

On one occasion, Nichols beat Colin Chapman at Brands Hatch and Chapman came up to ask what the secret of the engine was "If I told you you wouldn't believe me," came the reply, but I'm not going to tell you. Nichols response was not only the guarding of a trade secret, there was lust a touch of the shamed face there too, for he had raised the compression ratio to giddy heights by heating up the cylinder head and melting two brazing rods into each combustion chamber. It's the sort of blacksmith approach you wouldn't want to admit to.

Elva Mark II at the 1957 Watkins Glen Grand Prix

Malcolm Witts, Frank's mechanic, suggested making an overhead inlet valve/side exhaust valve head which gave 65 bhp at 5.700 rpm when fitted with twin SUs. Witts had the idea and Nichols saw the commercial possibilities and invested in it. When the prototype was completed, Harry Weslake undertook detail gas-flowing and brake testing as a favour. The production castings were made by Birmingham Aluminium Castings and they were finished off at Frank's business, the London Road Garage. The "LRG" head originally cost GBP 58, nearly doubled the output of the 100E engine and, it was claimed, could be fitted in three hours.

As most readers will know, "Elva" is a contraction of "Elle Va", French for "she goes", and it was a name suggested to Nichols by Jim Murphy, the brother of Dr Bill Murphy, a friend of Frank's. 1955 saw the first Elva car which was conceived by Nichols and Witts with Bill Murphy assisting with the bodywork and was intended to provide a show case for the special cylinder head, the notion being to race in order to drum up orders for the head - to sell heads - to make money in order to race.

The new car followed the general chassis layout of the CSM but had Standard Ten front suspension and steering while the rear was again a live axle but this time located by trailing arms and triangulated stabilizer rods mounted on rubber bushes.

In the best traditions of the Fifties, Frank was testing his car in chassis form at Brands Hatch when an onlooker, Dennis Wakeling asked if he could buy one. With the first sale the special builder becomes a constructor and so it was that the Elva Engineering Co Ltd was formed. The rolling chassis, less engine, gearbox and body, cost. GBP 350. The works could supply a neat but crudely styled aluminium body.

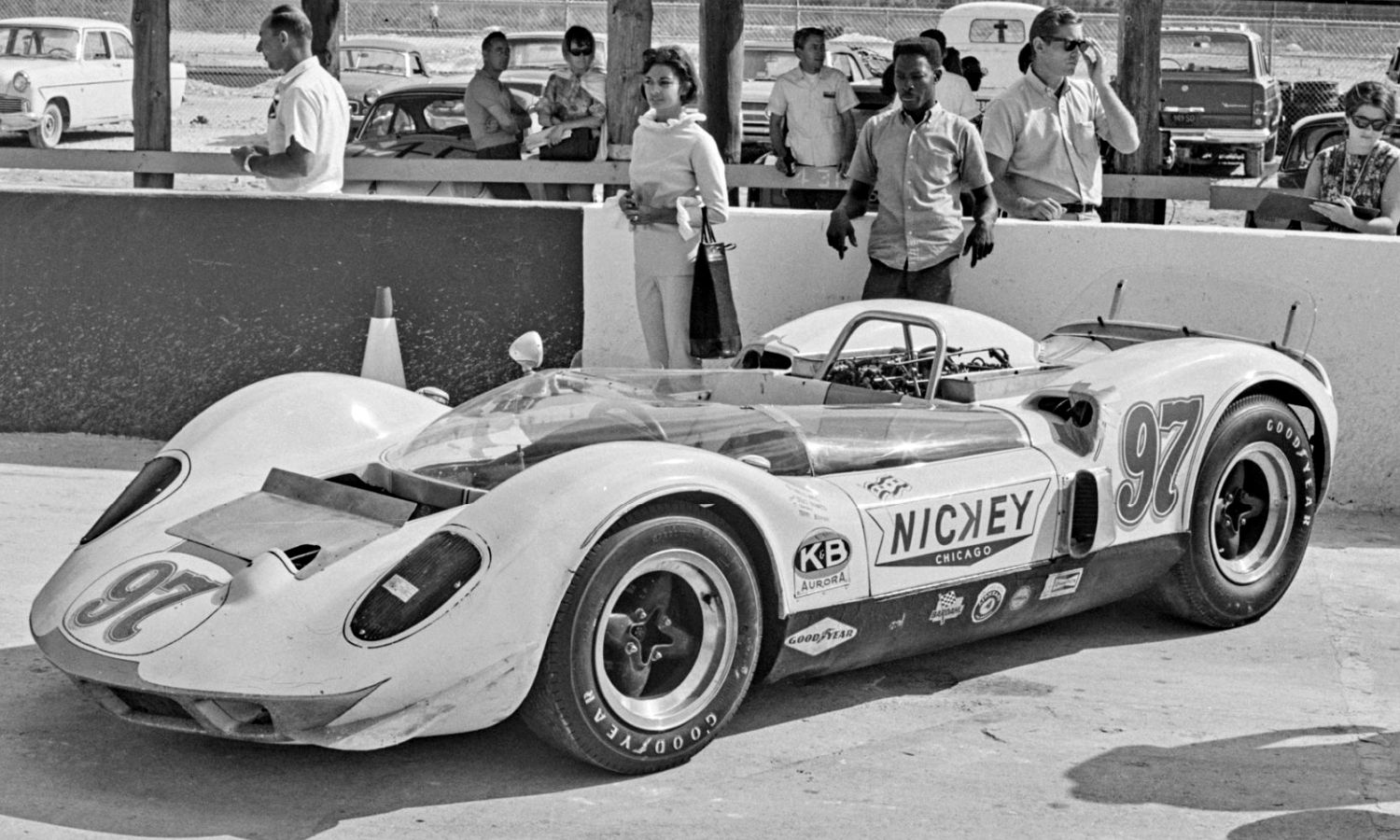

1965 McLaren Elva Mark I

Again Nichols made his car available to John Bolster and again JVB was able to enthuse about it. With a 1,098 cc Ford engine fitted with an Elva head and four Amal carburettors, Bolster achieved a pretty staggering top speed of 109,8 mph and found that it could be driven right on the limit all the time without ever becoming unstuck. He used it on the roads for a week, too. Bolster's road and track test helped the little firm establish itself but by mid-1955, the cars had already begun to make a reputation, both for speed and reliability, in the hands of Robin Mackenzie-Low, Peter Gammon and Les Leston.

It is thought that 20-25 cars were built in 1955. Six Mk1s and the rest Mk1Bs that had neater bodies, 15 with wire wheels and Elva 's own wishbone front suspension. More authorities claim 20 Mk1/1Bs but Roger Dunbar of the Elva Owner's Club puts the figure higher. The Club has had to work out probable production figures from the chassis plates of the cars it knows.

The Mk2 Elva that appeared in 1956 had detail modifications, a de Dion rear axle and was generally fitted with Coventry Climax FWA engines. Many, too, were clothed with Falcon fibreglass bodies. It was a good clubman 's car but no match for most Climax-powered Lotus Elevens or "bob tail" Coopers.

1957 saw the MkIll Elva, which was a further update and clothed with an aluminium body. While Lotus could call on the aerodynamic expertise of Frank Costin, the men at Elva relied on eye-experience and in the days when aerodynamics as applied to racing cars were still something of a black art, Elva lost out. You only have to compare the radiator orifices of the Lotus Eleven with the Elva III to see the difference. In racing terms, this meant that Elvas could be competitive on sprint circuits but lagged on speed circuits.

The MkIII was Elva's 1958 production sports racer and was a further refinement of the basic MkI concept though it was lighter and fitted with a bulbous aluminium body which made the little machine look quite bulky. Customers were offered a choice of engines. BMC Series "A" or "B" or Coventry Climax FWA and most chose the latter. Whatever the choice, transmission was through a four-speed MG gearbox. Elva's distinctive cast magnesium wheels first appeared on the MkIII.

Small sports car development had moved along at such a pace that a refinement of a 1954/5 design was not going to be competitive against the Lotus Eleven Series II that had been introduced at the beginning of 1957. Not only was the Eleven winning in Britain but it took two classes and 1-2 in the Index of Performance at Le Mans. It's not surprising then that only twelve MkIIIs were made, half the number of either of its predecessors.

The MkIII's best hope was to find a power advantage, something which Nichols attempted to do throughout Elva's history, beginning with the special head for the 1172 Ford and ending up with the involvement of BMW and Porsche. It seemed that such an advantage might be possible by using Archie Butterworth's air-cooled flat four engine. The deal was that Butterworth would supply the engine and a mechanic, Nichols would supply a cut and shut MkIII chassis and Archie Scott-Brown would drive the car.

Butterworth's engine had a unique inlet system, with swing valves operated by torsion springs. It was tricky to get running but once under way it delivered enormous torque and around 100 bhp per litre, then the Holy Grail of all engine builders. Unfortunately, Butterworth had been supplied with sodium-filled poppet exhaust valves which had been ill-machined and so, ironically, the engine constantly failed due to the failure of the conventional valves. When the engine failed, Scott-Brown was generally in the lead but we are talking about an engine which fails to complete five laps of the short circuit at Brands Hatch.

Finally, at the last meeting at Brands Hatch, the engine held together for long enough for the Elva-AJB to win a race. Nichols, however, had had enough of all the problems and did not take up his option to proceed any further with the engine, and since other potential users had been put off by the constant blow-ups, the AJB engine project passed quietly into history. What a pity this was for the bottom end of the unit was indestructible and the top end was sound as well, if given competent quality control by subcontractors.

During 1957, two significant things happened within Elva. The first was that "Mac" Witts left and his place as the man finally responsible for design under Nichols was taken by Keith Marsden, who later worked for Ford. Marsden had begun with Elva as a mechanic but had taught himself design and draughtsmanship through books and evening classes. As things turned out, he was destined to remain unknown to the majority of enthusiasts who always associated Frank Nichols alone with Elva, but he was unquestionably a gifted designer.

The other significant move was the decision to build a road car, which was an ambitious one given that Elva was only in its third year of existence. This became the ultimate responsibility of Peter Knott, introduced to Nichols by Archie Scott-Brown. Knott stayed with Elva for only a short time and the Courier was his only design for the company.

Frank says. "The Courier was conceived as a car for the road which could also take part in competitions and the ideal customer would have a weatherproof head and a pneumatic bum. The car came about at the prompting of Walter R. Dickson, our American importer, who ordered 30 cars and whose instalment payments allowed the car to be built and developed. Dickson later ran into financial difficulties and his problems affected us badly but I have to say that for a long time he did very well for us."

The Courier was a simple, light, car with a tubular steel chassis, fibreglass body, Elva front suspension, live rear axle and a BMC Series "B" engine tuned to give 72 bhp against the 68 bhp of the heavier MGA. It handled well and would accelerate from 0-60 mph in 9.2 sec and, more, was sold in the States for an initial price of the equivalent of GBP 1,150. A new factory was opened in Hastings to produce the cars and Couriers first appeared on the circuits was in 1958. It was an instant success and was soon winning racing on both sides of the Atlantic, indeed, the SCCA eventually had to modify its class structure to move the Courier up to compete against bigger-engined cars. It has to be said, though, that the Courier faced little in the way of real opposition in its class.

1958 also saw the MkIV being the first of the cars Marsden designed with Nichols. This was a crisply-styled sports racer powered by a Coventry Climax FWA engine driving through an MGA gearbox with, as before, a space frame and alloy drum brakes. The thing, which made it unusual, was the independent rear suspension in which the unsplined driveshaft served the function of the upper wishbone.

It is sometimes said that the MkIV was the first racing car to use this system but the fact is that Eric Broadley was developing the Lola Mk I on similar lines at the same time and the Elva happened to be finished a few weeks before the Lola. Ian Raby drove the prototype in Britain without scoring any notable successes, though the car did well in the States and revived Elva's fortunes in small capacity sports car racing by selling 32 examples altogether.

The MkIV's rear suspension shows that Nichols and Marsden were innovative and it was hard luck that Broadley had brought out his Lola at the same time for that was the cream of small front-engined sports cars. Without Lola on the scene, Elva should have been able to have beaten Lotus in 1959, for the Lotus Seventeen was something of a disaster.

Nichols really needed a good works driver and, in October 1958, nearly secured the services of Peter Ashdown who, after testing the car at Brands Hatch, hung around the circuit and was invited to try Broadley's prototype Lola. Nichols never did find the one special driver with whom to form a team. The MkIV was Elva's production racer for 1959 and it began well in the States by scoring a 1-2 in class in the Sebring Twelve Hour race. That success led to orders in the States but in Britain 1,100 cc racing was all about Peter Ashdown and his Lola. This was a shame for Elva for the MkIV was probably better than either the Lotus Eleven or seventeen. As soon as Nichols was in a position to beat Chapman, Broadley came along.

Midway through 1959, the MkV appeared. an updated. even lower, development of the MkIV. The prototype was put in the hands of Mike McKee, an exciting driver who seemed certain either to wrap himself around a tree or else become an F1 ace, but even McKee's talent and enthusiasm was no match for the increasing number of Lolas which were appearing. McKee was able to mount a challenge but never to beat them. The MkV became Elva's production sports racer for 1960 and, as before, it did quite well in the States, selling a total of 10 cars, but 1960 was to see a dramatic change of emphasis in racing at a junior level.

The 1960 Formula Junior season was the most significant season in the history of post-War motor racing, indeed, perhaps the most significant season ever. Previously, the small specialist makers in each country had rarely competed directly against each other. The number of times when, say works Lotus Elevens had met works Stanguellini 1100s were remarkably few. Formula Junior provided the opportunity for all the small companies that had catered for national racing, to compete against each other internationally.

Always one to spot a trend, it was in mid-1959 that Nichols had Elva build an FJ car before any of his rivals though Elva was not the first British maker of an FJ car. It was a simple, slim, front engined car with Lockheed drum brakes (outboard at the front, inboard at the rear), coil spring and wishbone front suspension and independent rear suspension with lower single arms, fixed-length drive shafts and trailing radius arms. Initially a tuned BMC Series "A" engine was fitted and the engine drove through a four-speed BMC gearbox via a propshaft articulated to pass downwards between the driver's legs and so through a transfer box to a centrally mounted differential.

On September 6th 1959, at Cadours, France, against the best Continental opposition, Bill de Selincourt scored a memorable victory. Then at Brands Hatch on October 4th, Mike McKee, De Selincourt, Chris Lawrence and Peter Jopp took the top four places in the first British race to be organised specifically for FJ cars.

The big event of the year, though, was the Boxing Day Brands Hatch meeting with new cars from Lotus, Cooper, Lola and Gemini, driven by Jim Clark in his first single-seater race. Peter Arundell and Chris Threlfall in the works cars both had Mitter-tuned three-cylinder two-stroke DKW units that were powerful but temperamental. The new cars from Lotus, Lola and Cooper all had teething troubles and Arundell won easily with Threlfall in third place.

The most important race to win is always the last one of a season and Elva received an astonishing number of orders. Some have written that as many as 150 FJ's were produced but the Elva Owner's Club believes that 69 is the more likely figure with an additional 15 Scorpions. Within four months, however, the Cooper and the Lotus 18 had established themselves as the cars to beat in Europe with the Lola Mk II emerging as perhaps the best of the front-engined cars.

When Elva later ran into financial difficulties, 15 Scorpions were built by one of Frank's companies Ryetune. These were re-bodied front engined FJ cars but the change of name and body was necessitated by the delicate financial situation. Most had DKW engines.

In looking for a power advantage, Nichols had passed over the Ford 105E engine that had just been announced with the Anglia and went instead for DKW. Chapman had meantime commissioned Cosworth to develop the Ford unit and when Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin produced a winner, Chapman insisted on exclusivity for Lotus buyers. The engine perhaps flattered the Lotus 18.

Across the Pond, though, Charlie Kolb's Elva-BMC swept all before it and became perhaps the most successfully Elva built. Jim Hall and Hap Sharp scored many wins in their DKW-powered cars and Pedro Rodriguez drove a Scorpion.

Although it was clear that the rear-engined revolution had arrived, Elva was so busy fulfilling its orders that it was quite late in the year before the second generation Elva FJ car made its debut. This was in the British Empire Trophy at Silverstone on October 1st. In appalling conditions, Chuck Dietrich, on his first visit to the circuit, brought his BMC-powered car home behind the Lotus-Fords of Henry Taylor and Peter Arundell, beating the likes of Trevor Taylor and Denny Hulme.

While the first FJ car was helped by being the first series-produced British car on the scene, the new car had to fight for a place in the sun against a new establishment in the formula. It still sold but not at the heady rate of the original car. By the end of 1960, though, Elva was producing an average of four to five cars a week with Couriers accounting for around three quarters of the sales, with the rest being divided between the FJ car and the MkV sports-racer. Most were going to the States and Frank was a regular trans-Atlantic commuter.

In 1961, Elva ran into severe financial problems and so the old company was liquidated. With financial backing from Carl Haas and others, Frank was able to set up Elva Cars Ltd and the Courier project was sold to Trojan, which was then trying to diversify. Somewhere between three and four hundred Couriers had been made in the Hastings works in the previous three years. Just 210 were to emerge from Trojan's Croydon works over the next four years. Despite passing through various updates and revisions, the Courier project was dead within four years.

Working from smaller premises in Rye, Elva got back into its stride, though on a much-reduced basis. The rear-engined FJ car, the "200" series, and the MkV, a remarkably low updated version of the IV, formed the 1961 range while Keith Marsden was pressing ahead with two new models. Neither of these cars sold well, perhaps 20 Juniors were made and ten MkVs. Neither was a particularly successful car though Chuck Dietrich who scored a total of 65 wins with the various Elvas he owned, managed ten consecutive victories in the Mid-West with his Junior.

The first of the "new" Elvas was another FJ car, the "300" series, which was intended as the 1962 customer car and which may have been the lowest single-seater production racing car ever made. It appeared at the Whit Monday Goodwood meeting but the driver, Chris Meek, crashed at the chicane doing no good either to himself or the prototype. Six were built in all but none scored any notable successes except in the hands of Chuck Dietrich.

Based on the FJ car was the MkVI sports car that used a 100 bhp Coventry Climax FWA engine developed by Henry Weslake. This appeared just before the Lotus 23, which featured Lotus twin cam version of the Ford 105E engine and which proved the better long-term bet. Chris Ashmore, in the first MkVI, caused a sensation at the Boxing Day Brands meeting by embarrassing Graham Hill's three-litre, rear-engined, Ferrari Testa Rossa, sharing the fastest lap with it.

The MkVI had a low slippery shape (the wheel arches were higher than the windscreen), with two little nostrils to take in air, a light but very stiff triangulated spaceframe, wishbone, coil spring and damper front suspension along the lines of the MkIV. While rivals were specifying disc brakes, Marsden stuck with Lockheed/Alfin outboard drums at the front, inboard drums at the rear. A number of engine options were available but all drove through a modified VW gearbox. It was a decided advance in small sports racing car design - until the Lotus 23 appeared shortly afterwards.

Though results suggested otherwise, there was not a great deal of difference between the Elva and Lotus chassis in terms of merit, the main difference lay in the engines. Chapman had been typically astute in his provision of a suitable power unit and Nichols had to hunt around to find an answer.

1962 was a mixed season. Paddy Gaston crashed the works MkVI early on at Oulton Park and Bill Moss, who took over the drive, injured himself badly in the Formula Junior car at Reims. Still, Gaston was able to win his class in the Aintree International and Chris Ashmore and Robin Carnegie won the two-litre class in the Nürburgring 1,000 kms. Dizzy Addicot, using an Alfa Romeo engine in his MkVI trounced strong Lotus opposition to win the 1,300 cc class in the Guards Trophy sports car race at Brands Hatch in early August and, at the Boxing Day Meeting, brought a 1.5-litre Alfa Romeo-engined MkVI home second to Mike Beckwith 's Lotus 23 in the Silver City Trophy race.

Twenty-eight of these cars were made, with two-thirds going Stateside. Meanwhile Elva was acting as a consultant to Trojan and that year saw a Mk3 Courier which could be supplied complete for GBP 965 or GBP 716 as a kit. There was the promise of a restyled Courier, Mk4,in the offering. Unfortunately, to increase cockpit space, Trojan moved the engine of the Mk3 forwards with the result that the handling was diabolical. In its capacity as a consultant, Elva moved the engine back where it ought to be and restored the handling at some cost to comfort.

One can understand why Trojan made the modification, there is a larger market for comfortable sports cars than there is for uncompromising ones and the aim was to produce over 500 Couriers a year. What is more difficult to understand is why Trojan was apparently baffled when a conscious change in weight distribution altered the handling characteristics of the car. Whatever the reasons behind Trojan's thinking, Keith Marsden pressed ahead with the Mk7 sports racer in Rye.

The Mk7 Elva followed similar lines to the VI but beneath the smoother, lower fibreglass shell there was a new car. The spaceframe had been lightened and, at 73 lb complete with brackets, it was 12lb lighter than the MkVI. Front suspension was new too, with unequal wishbones ball - jointed to a magnesium upright and, at last, drum brakes gave way to discs. Thirteen inch wheels replaced 15 inch wheels, reducing unsprung weight and allowing a lower, neater, bodyline. At the rear fixed length drive shafts gave way to splined shafts with an anti-roll bar.

In production terms the VII was highly successful, 29 were built in Mk VII guise and 42 of the lightly revised VIIs were made and these were fitted with a wide range of engines, including Coventry Climax, Ford and Osca but two are particularly interesting: BMW and Porsche. Nichols helped bring BMW back into motor racing as an engine supplier after the Bavarian company had begun its recovery from near bankruptcy in the Fifties. A lot of background work went into the deal, the object of which was to give Elva a distinct power advantage over its rivals.

Elva, Alex von Falkenhausen of BMW, Frank Webb of Nerus Engineering and Ted Martin, who designed the dry sump conversion, came up with a racing two-litre engine, based on the 1,500 cc unit which first appeared in 1950. This gave 182 bhp at 7,200 rpm and 156lb ft torque at 5,000 rpm and fed through a five-speed Hewland HD5 gearbox.

At the same time that the BMW deal was being worked out in 1962/3, Nichols, Haas and Ollie Schmidt an American Porsche distributor, were making overtures to Porsche for the supply of the flat four 1,700 cc dohc engine. The original idea had been Schmidt's and it was a bold one for Porsche had previously turned down such overtures. Dr Ferry Porsche, supported by Huschke von Hanstein, the racing director, and Herbert Linge, Porsche's test driver, agreed to supply the engines and one must ask why.

The reason they gave is that Elva was already well known and respected; there had been lots of racing Elvas in Germany, and some Couriers. I suspect, though, that the real reasons were that Porsche was looking for further expansion in the American market and also wanted to monitor British chassis and suspension developments for Porsche bought one of the cars and fitted it with an eight-cylinder engine. With it, Herbert Muller finished second in the 1964 European Hill Climb Championship - behind Edgar Barth 's similarly-engined Porsche RS Spyder. Muller was driving to team orders and so it was just possible that he might have won the Championship, at any rate the 1965 two-litre Porsche appeared to have some Elva influence.

A Mk 7 chassis was beefed up to accept the Porsche engine and five speed gearbox and was completed on August 22nd 1963, arriving in the States just before the Elkhart Lake Road America 500 race on September 8th. In its maiden race it faced 60 other entries of the order of Cobras, Ferraris, E-Type Jaguars and Porsches. Bill Wuesthoff. a noted Porsche exponent, promptly put the car on pole!

Everything had been done at such short notice that a second driver had not been signed but no fewer than 11 other entries had been nominated as a relief driver on the grounds that the car of at least one of them would be out of the race by the time Wuesthoff was ready to hand over. Dr Sodt's famous law was operating at full strength, however, and the cars of all 11 nominees were going strong. Permission was then sought from Roger Penske, and granted, to allow Augie Pabst to take over after his stint in Penske 's Ferrari GTO.

Pabst had not even sat in the car at the point he took it over but he swept on maintaining Wuesthoffs lead and the car scored a memorable victory, even though it went largely unnoticed here. It was the first time that so small an engined car had won the RA 500 and the race itself was second in prestige only to Sebring. It was hailed as a "David and Goliath" act and 15 orders were immediately placed for replicas.

Nineteen Elva-Porsches were made all told including the one bought by the Porsche works that was given a Porsche designation. Though these were successful in the USA not one of them was bought in Britain and, indeed, only one ever raced here. That was in the 1963 Boxing Day Brands meeting and Mike Beckwith brought it home a lacklustre fifth on a greasy track.

At the Racing Car Show in January 1964, the Mk VII-BMW was shown for the first time, Tony Lanfranchi was announced as the works driver and for the first time for Elva, this was a full works drive. Lanfrenchi was to repay this faith with a good season in his BMW-powered car, eventually emerging as the Autosport Champion. Trevor Taylor came close to winning the Tourist Trophy with another Mk VII, but was scampered by dynamo failure. Lanfranchi says now that the Elva was a good car but, in his opinion, not quite up to the contemporary Lotuses and Brabhams.

At the same time that the 1964 racing plans were revealed it was also announced that Trojan had taken over Elva. Trojan had ambitious ideas, which included F1, and also had the resources to implement those ideas. It must be remembered that long after Nichols departed, Trojan did build F5000 cars and an F1 car, designed by Ron Tauranac.

Trojan was still producing the Courier in Croydon, though at a rate of only about one a week, Elva was making Mk 7s at a similar pace, and the first car of the Trojan-Elva marriage was conceived, the GT 160. The plot of this car was simple, and it was brilliant. An Elva Mk7 chassis, a two-litre BMW engine and a GT body designed by Trevor Fiore and built by Fissore of Turin. When it was shown at the Earls Court Motor Show in October 1964, it created a great deal of attention, was widely acknowledged as the "Star of the Show", and many orders were placed.

Unfortunately, the idea was impractical. If the chassis had to go to Italy to be bodied, then there always had to be a comparatively large number of cars "in the pipeline" and a small company could not support that. The new Labour Government imposed a 15% import surcharge that immediately raised the price of the car. The CSI imposed a new ground clearance regulation that meant that the 160 GT would have to be re-designed and the Fissore body was too heavy anyway.

Frank says now that his idea was to fit the car with a fibreglass body designed and built in England and with hindsight, says that the ideal solution would have been to hand it over to Ogle Design.

Only three 160 GTs were made, though Elva had been geared up to make the 100 minimum then required for homologation. One of these cars was entered into a number of classic races by Anglian Racing Developments, but it failed to finish any.

An updated version of the Mk7, the Mk8, appeared at the end of 1964 and a total of 21 were made: nine Mk8s and 12 examples of a revised "S" model, but then the company took a new direction with the construction of customer versions of Bruce McLaren 's McLaren M1 sports-racing design, the forerunner of the McLaren Can-Am car. Most customer McLarens were built by Trojan/Elva up to 1971. Nichols was disenchanted, he'd seen his company grow, fail grow again and then gradually slip away from his control. Though the name "Elva" was associated with McLaren sports-racing cars for a while it was eventually dropped but by that time Keith Marsden had gone to Ford and Nichols had resigned for health reasons, as they say in diplomatic circles.

With Elva celebrating its 40th anniversary in 1994 and the Historic movement gaining greater ground both here and abroad, Nichols has been in some demand as guest of honour at various meetings mainly in the States. His cars are as successful there in Historic racing as they were when they were new but, the irony continues, they are not often seen in British Historic racing.

Elva attracted some well known drivers through the 1950's and 60's and included: Archie Scott-Brown, Mark Donohue, Tony Lanfranchi, Bruce McLaren, Bobby Rahal, Carl Haas, Bernie Eccelestone, Robin Mackenzie, Les Leston, Stuart Lewis-Evans and Alex McMillan.

Text by Motor Sport Magazine

We are looking for the following cars. If you do have any of the below listed vehicles - and you are ready to sell - please Contact Us.

| Courier |

|---|

| Mark I - IV |

| Racing |

| Mark I - VIII |

| Formula Junior |

We buy, sell, broker, locate, consign and appraise exceptional classic, sports and collector Elvas'

Contact us when you are serious about buying a fine Elva Motor Car or to arrange a free and confidential valuation with a view to selling.