Ford Motor Cars

People can have the model T in any color-so long as it's black

The Model T is a legend. It created a long series of stories, jokes and in its day, even some broken arms. It gave the words flivver, jalopy, and tin lizzie permanent place in the American language and it "put America on wheels."

By now time has surrounded it with an aura of romance and nostalgia, but anyone who ever had to cajole, wrestle with, and drive a Model T will easily remember the cantankerous nature of the machine.

It was hard-riding, skittish, and susceptible to high fevers. To crank this car was an athletic ordeal, ending with a bone-wrenching backlash of the crank handle. The planetary transmission always had a mind of its own, and the Model T, even in neutral, trembled and strained at the leash.

But the T, changed the face of America and demonstrated to the industries of the world a practical method for mass production. As a by-product it educated an entire generation of backyard mechanics and tinkerers. The Model T was a do-it-yourself car and was quite logically the product of a do-it-yourself man.

Henry Ford was a typical Yankee inventor, a man who tinkered with mechanical parts, used "rule of thumb" design, and displayed a practical genius for machinery. Born in 1863, he spent his youth on his FORD father's farm near Dearborn, Michigan. He hated farming, but his natural instinct for machinery made him the young handyman for all the farmers in the area.

He repaired clocks, pumps, and the rest of the usual farm equipment. This divergence from farm chores angered his father, and the continuing disputes ended in his running away to Detroit at the age of sixteen. There, Henry Ford became a machinist's apprentice and finally a fully qualified mechanic. He worked on marine engines and the standard industrial steam and gasoline engines of the time.

By the time he was twenty-four his rebellious spirit had cooled a little. He returned to the farm, married, and tried to settle down. But the call of machinery proved too strong and his second hegira was final. With his new wife, Ford returned to Detroit and became an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company. It is quite possible that he would have worked happily for the light and power company the rest of his life, but in 1892 a fire was lit in his mind by the construction of the first automobile in America by Charles and Frank Duryea.

From the moment Ford saw the Duryea he knew what his life work would be. Although he held down a ten hour a day job at Edison, he built a workshop in his backyard and started constructing a car at night. With some help from Charles B. King, a fellow inventor, Ford finally completed his first car in 1896.

It was a strange affair-four bicycle wheels and an old buggy frame with a four-horsepower two-cylinder engine. Almost everything was made by hand. The cylinders were old steam pipes and the transmission a leather belt. There was nothing new about this first Ford; it represented no advance in automotive technology; it was not very efficient; it could not back up; it had only one shining attribute, it ran!

After enjoying the satisfaction of success, Henry Ford sold his car for two hundred dollars and went back to his shop.

By 1899 he had constructed three cars and was beginning to be recognized as an automobile engineer. This fame naturally led to his being selected as the chief engineer of a new concern, the Detroit Automobile Company. In a year it failed.

This did not stop Ford. In 1901 he organized the Ford Automobile Company, but that too lasted only a year. Both ventures failed for an understandable reason. Henry Ford was not, at that time, interested in passenger cars. He wanted to build a racing machine and drive it himself. All his time was spent in designing high-speed equipment.

Although he was now out of a job, he continued his work. Financing was taken care of by Thomas Cooper, a wealthy former bicycle racer; expert engineering advice was supplied by Harold Wills. Ford, Wills, and Cooper began to attract attention by producing a series of racing cars.

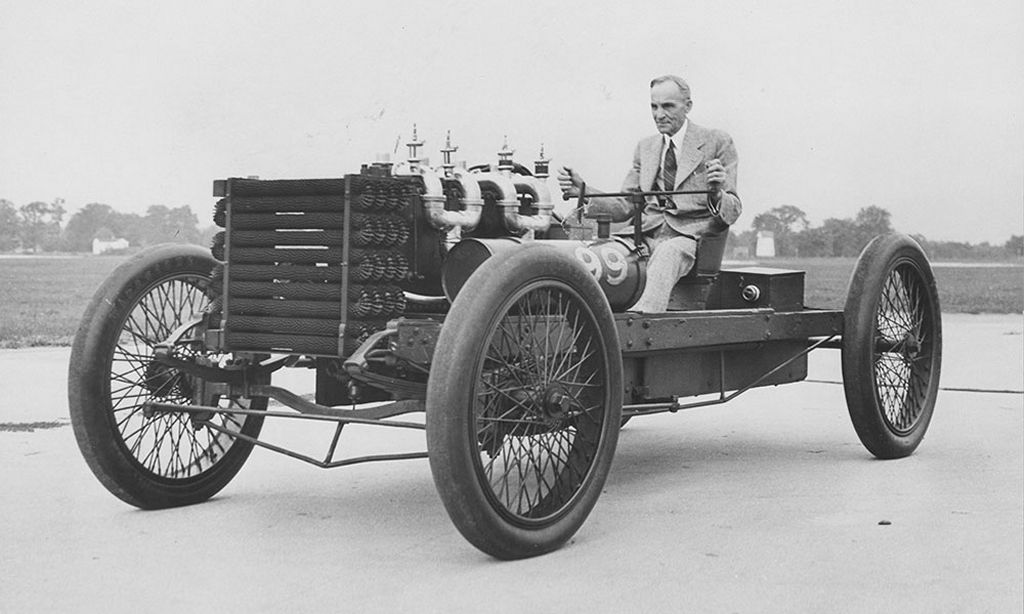

Ford himself was the driver and the newspapers of the day called him a "speed demon." By 1902 the famous 999 was made. It was a powerful brute and none of the three was willing to race it. They interested another bicycle racer in the big red machine and he drove it to victory in its very first attempt. This driver was Barney Oldfield: he had won the first race he entered. Even more astonishing, it was the very first time he had driven a motor car!

It was the 999 that gave Ford his real start. Alex Malcomson, a wealthy merchant, wanted to invest in an automobile company. The sound design of the racer attracted him and he offered to back Ford. This was the beginning of one of the largest industrial empires in the world. The two men came to terms rapidly, named the firm the Ford Motor Company, sold stock, and got under way.

Ford brought Wills and Cooper with him and Malcomson contributed James Couzens as business manager. The best machine shop in Detroit at that time was being run by John and Horace Dodge (who later made a car of their own), and Malcomson lost no time in convincing them to join the Ford Motor Company. This combination of financial resources plus inventive talent and technical ability was unbeatable.

The first car that the new company made was called the Model A, and this 1903 product appealed to the public immediately. It was even sold in Wanamaker's Department Store in New York City.

But the Ford chiefs felt the need to acquire prestige for their name, and they went about it in the way that was to become traditional speed. The 999 was taken out of the garage, retuned, and prepared for an attempt at the Land Speed Record.

Henry Ford himself elected to drive the speedster and in the dead of winter he took the car out on the ice of Lake St. Clair. Along a track of cinders and ashes, Ford and his mechanic, Edward Huff, piloted the big red machine to a speed of over 90 mph. This was a new record and all eyes and checkbooks now turned toward the new passenger Fords. The next most successful Ford was the Model N which appeared in 1906, but Henry Ford was already engrossed in plans for what eventually became the famous Model T.

The concept behind the Model T was much more important than the car itself. Henry Ford wanted to build a car that the average wage earner could afford and he was especially interested in the problems of the farmer. Originally he saw the Model T as a utility vehicle for the farmer, with a removable engine that could be hooked up to run saws, pumps, and all manner of farm equipment. But the car had to be made available at a reasonable price.

The only way to achieve this was to design a light-weight car that could be put together rapidly from parts that were so standardized that any item could fit any car. In other words, mass production on an assembly line basis. Henry Ford's concept and the success of that concept revolutionized the automobile industry, as well as every other big industry, and changed the social structure of America.

The idea of mass production stems from the minds of many men. Like the automobile itself, it came about as a result of logical steps. The first important stage was reflected in the accurate machine tools of Sir Joseph Whitworth. This British engineer introduced the first system of precise measurement early in the nineteenth century. For the first time in human history the various fractions of an inch were plotted to exact points. Whitworth also invented a machine that could measure to the millionth part of an inch.

This precision plus his insistence on a system of uniform screw threads finally allowed machine-tool users to turn out mechanical parts that were exact duplicates of each other. The development of accurate tools resulted in one of the first examples of mass production. Samuel Colt and his engineer Elisha Root set up the manufacture of the Colt revolver in a completely standardized manner. Parts were made in large quantities and then were assembled with the assurance that any given group of components would work together without additional machining.

This system of standardization was applied to the automobile by Henry Ford. Then he added the revolutionary step - the moving assembly line. It began with a job analysis that reduced each function to a set of basic units, and then arranged the machine tools in production order.

This meant that an item progressed logically from one operation to the next. A series of troughs connected the machines and the parts slid from one to the other by gravity. But each car was still assembled in one place by specialized "work gangs" that moved from chassis to chassis, and by 1913 the Model T still took twelve and one half hours to complete.

Ford and his engineers installed moving feeder lines to bring the parts to the men and this device resulted in an astounding idea. Ford, in a flash of inspiration, decided to move the chassis along the factory floor with specialized men and parts-waiting at the proper points. He tested the innovation by dragging a chassis with a rope, and his men put the car together twice as fast!

This was a major breakthrough, and in a very short time the Ford Motor Company installed overhead endless conveyor belts. The entire assembly now swung smoothly through the air with smaller subsidiary belts feeding parts all the way. In 1914 a Model T was built in one hour and a half. Then machine tools were devised that could perform many simultaneous operations and in 1920 the Ford Motor Company was producing Model T's at the rate of one a minute.

As though that were not a miracle in itself, Henry Ford continued to perfect his system. His driving obsession resulted in a record of production that is unequalled even today. On October 31, 1925, a car came out of the Highland Park plant at the rate of one every ten seconds! That particular working day produced 9,109 Model T's.

This achievement changed the pattern of American industry. When mass production spread to every type of appliance, the economic picture of the country changed radically. In large part, the high American standard of living can be attributed to the development of mass production. Aside from the increase in living standards, it brought drastic changes,.good and bad, in the way Americans work and live.

The heyday of the skilled journeyman machinist was over and the new factory worker became a specialized individual who needed only the ability to operate a single machine efficiently. Now there were many new jobs available and industrial cities grew immensely larger.

The rapid change in the American economy was chaotic but a great beneficial factor finally emerged. Mass production techniques not only turned out products in huge quantity but at costs that were much lower, and the average American could now afford many things, especially automobiles, that he could never buy before.

This was Henry Ford's great contribution to America and the world. With success, Ford became a rigid and unbending boss, running his great company almost as a feudal state. Ford's rigidity extended to the design of the cars as well. The concept of the Model T called for a never-changing design: the customer could have any color he wanted "as long as it was black." Henry Ford saw his car was good and he felt that the public should continue to accept it just as he made it.

By the nineteen-twenties Americans began to reject the Model T, but Ford clung stubbornly to his basic idea. In 1922 he bought Lincoln to compete with the handsome Packard, but this did not bring in enough Ford revenue. He also discovered that a high-quality car could not be produced with quite the same techniques as the simpler, more spartan Model T.

William S. Knudsen, who had spent some time as a Ford executive and had left thoroughly disgruntled, began to cut into Ford's market with the Chevrolet produced for General Motors. The Chevrolet offered much that Ford refused to add. Knudsen provided four-wheel brakes, real windows instead of side curtains, easily demountable balloon tires, an efficient cooling system, reliable battery ignition, a positive transmission all of this, in a faster, better-looking car.

But Ford stood firmly against design progress. He seemed to believe his creation was perfect. It was, in its time, but by the twenties it was outmoded and outengineered. With the company in financial straits, he finally agreed to make changes. In 1926 the Model T was refurbished and even appeared in several colors, but it was too late. Early in 1927 the Model T made its last production run. A mass retooling plan was put into effect, but it was not until 1928 that another Ford appeared.

The new Model A was a fine car, with one of the first applications of safety glass in an automobile, but Henry Ford repeated his pattern. This car remained unchanged for five years while Knudsen brought out a six-cylinder Chevrolet with full synchromesh transmission, and Walter P. Chrysler introduced the Plymouth with hydraulic brakes and a rubber-mounted "floating power" engine. Once again the Ford Motor Company was forced to retool and redesign, but one should remember that the Model A was so well-made that even now many can be seen running smoothly on our highways.

Ford saved his fortunes by producing a V-8 in 1932. This time he was willing to make improvements; and year after year his V-8's showed steady engineering progress. The original model made in 1932 was an extremely fine machine and is still used as the basis for many hot-rods.

The real importance of the Ford V-8's lay in their snappy performance. They offered good road speed and jolting acceleration at a modest price. These unassuming cars could pace mile after mile with bigger, more expensive American automobiles. Historically the V-8 was the first fully mass-produced, low-priced V-8 in the world.

In keeping with the trend toward greater power a new line was added in 1939. This was the Mercury. Essentially it was a larger Ford, with somewhat similar styling. But the bored-out engine gave it exciting acceleration. Throughout the country local police departments earned large percentages of their budgets by fining overzealous Mercury owners.

After World War II the Ford cars began to follow the trend to uniformity that swept like a wave over the entire American automobile industry. Fins sprouted from the rear, the body lines became box-like and a host of willing push-button gadgets appeared to do the driver's bidding. The horsepower climbed as the engines grew and gas consumption figures rose like the temperature of the old Model T on a hot day.

A sad experiment named the Edsel was undertaken. It can now be called "the car that appealed to nobody." The Edsel was the result of a long research program that overemphasized flashy styling and luxury gadgets and managed to forget economy and many other factors of the competitive market.

Then came the Thunderbird. It started as a two seater sports car with a large engine. But it was really neither a sports car nor a passenger machine. The compromise was too great. As a sports car it had speed but none of the precision handling and swift cornering ability that the European machines have. It was saved by enlarging it into a plush four-seater with expensive appointments to appeal to buyers who want a sporty looking car with American comfort.

But the true spirit of the old Model T was resurrected in the Falcon in 1960. The Ford Motor Company produced this compact car to meet the ever-growing incursion of foreign imports and to satisfy the public's desire for a small machine. Here at last was a small, lowpriced American car that was economical to operate and had clean, simple styling.

The fat overgrown dowager appearance was gone from this Ford. It had a neat functional look that appealed to many buyers, and its compact size promised easier parking for harassed city dwellers. It seemed to herald a return to the old policy of making a car that was basically transportation and not a traveling living room.

When Henry Ford died in 1947 he left a huge and thriving industry to his family, but he left a larger legacy to the world. When he first began his system of assembly line mass production in the early years of the twentieth century his slogan was "Watch the Fords Go By." Today, thanks to him, we can say, "Watch the Cars Go By."

We are looking for the following cars. If you do have any of the below listed vehicles - and you are ready to sell - please Contact Us.

| Ford |

|---|

| GT 40 |

| Mustang Boss |

We buy, sell, broker, locate, consign and appraise exceptional classic, sports and collector Fords'

Contact us when you are serious about buying a fine Ford Motor Car or to arrange a free and confidential valuation with a view to selling.